Swan song and death dive

|

| The planet Saturn, viewed by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft during its 2009 equinox. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute. |

Its eventual destination was the gas giant planet Saturn and is retinue of moons and rings, but it went the long way round: first two loops of Earth's nearest neighbour - the inner planet Venus - followed by a close encounter with Earth and it's moon. These encounters were planned to increase the craft's velocity and haste its passage through the asteroid belt towards Jupiter - the king of planets.

Jupiter's gravitational heft then slingshotted the probe, at speed, towards its eventual goal - the ringed majesty of Saturn. Cassini attained orbit around Saturn on July 1 2004, almost seven years after its departure.

The space probe was a chimera - two craft joined at the hip. A lander - the European space agency's Huyghens probe was designed to be jettisoned to land on Saturn's largest moon Titan while the orbiter - Cassini - was designed to repeatedly circle the planet and visit its moons and rings.

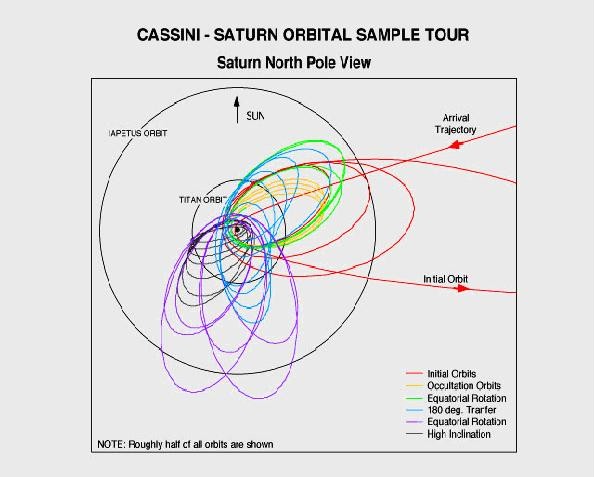

However, ``circle'' is both a misnomer and understatement, for the celestial mechanics at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory had planned an exquisitely choreographed game of space billiards, in which they used close encounters with Saturn's largest moon Titan to bend and twist the path of Cassini around Saturn so that it could examine each of Saturn's large moons (and many of its smaller ones too) and rings from the best viewing positions achievable.

|

| Celestial billiards - the initial part of Cassini's tour of the Saturnian system |

Saturn is not perfectly spherical - because of its fast rotation it bulges at its belly and this makes its gravitational field bulge too. And this bent out of shape gravitational field tugs at Cassini (along with minor tugs from its larger moons). This means that from time-to-time it must fire small thruster rockets to adjust its attitude (i.e. where it is pointing) and also to make sure it arrives just in time to obtain the optimal pull from Titan's gravitational field to get to its next destination on time.

The supply of propellant is finite, and by mid 2017 Cassini will be running on empty after which it would quickly become impossible to guide it or predict its position with any accuracy. Which would be neither here nor there, if it wasn't for the fact the amongst all of the amazing discoveries Cassini has made, perhaps the most amazing are the fountains pluming up from the moon Enceladus.

Tiny Enceladus, with a radius of just 252 km has an ocean larger than all of Earth's hidden beneath its white frozen surface and Cassini has flown through fountains of frozen water droplets, carbon dioxide, salts and silica emanating from its surface - tasting the salt tang of its hidden seas with its instruments.

But with liquid water comes the possibility of life. So it was decided that it was imperative that Cassini should be disposed of in such a way that there could be no chance of cross-contamination of Enceladus and its ocean with Earthly microbes.

So as its swan-song, Cassini will dive between the rings and Saturn in a final daring encore of twenty weekly orbits followed by a final flourish by this ultimate celestial trapeze artist - a deep, fatal dive into the atmosphere of Saturn on the 15th of September. Even in its final minutes, the probe will continue sending telemetry and data to Earth until it is crushed by the pressure of Saturn's atmosphere.

Does a space probe need an epitaph? Surely Cassini warrants one, and I can't think of any better than the American poet Robert Frost's lines:

"I took the path less traveled by, // And that has made all the difference."

Comments

Post a Comment